Reading Why another programming language?

Between Python, R, MATLAB, and others, there are many excellent programming languages suitable to data science. So why did Jeff Bezanson, Stefan Karpinski, Viral B. Shah, and Alan Edelman decide in 2009 to write a new language?

The answer lies in an aspect of the history of programming languages that Rust developer Graydon Hoare explores in a very interesting post. In short, it comes down to the fact that the vast majority of computer languages fall into two categories: compiled languages and interpreted languages.

Two types of programming languages

Compiled languages

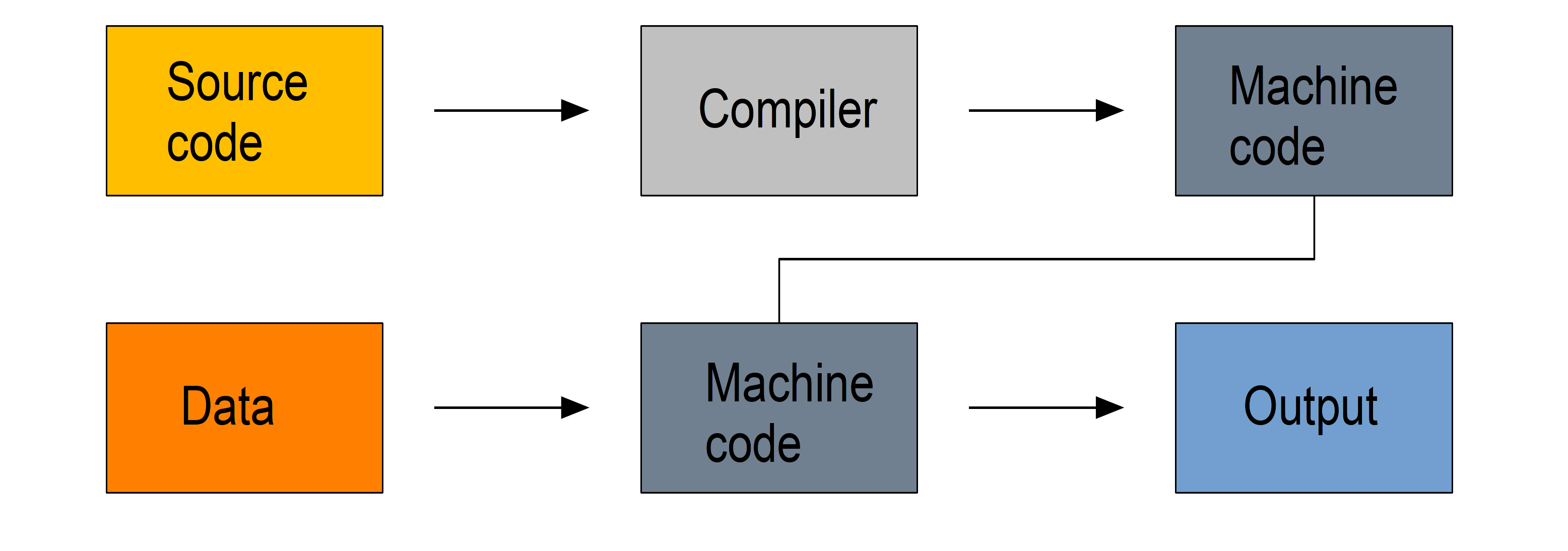

Compiled languages work in a two-step process:

- first the code you write in a human-readable format (the source code, usually in plain text) gets compiled into machine code,

- then this machine code is used to process your data.

So you write a script, compile it, then use it.

Examples of compiled languages include C, C++, Fortran, Go, and Haskell.

Because machine code is a lot easier to process by computers, compiled languages are fast. Once you have a script, running it is extremely efficient.

The two step process however makes prototyping new code inconvenient and exploration of the data tedious. If each time you want to play with the data or visualize it in one way or another, you need to recompile the script before running it, you may not do as many whimsical explorations. These languages are also hard to learn and debugging compilation errors can be challenging.

Interpreted languages

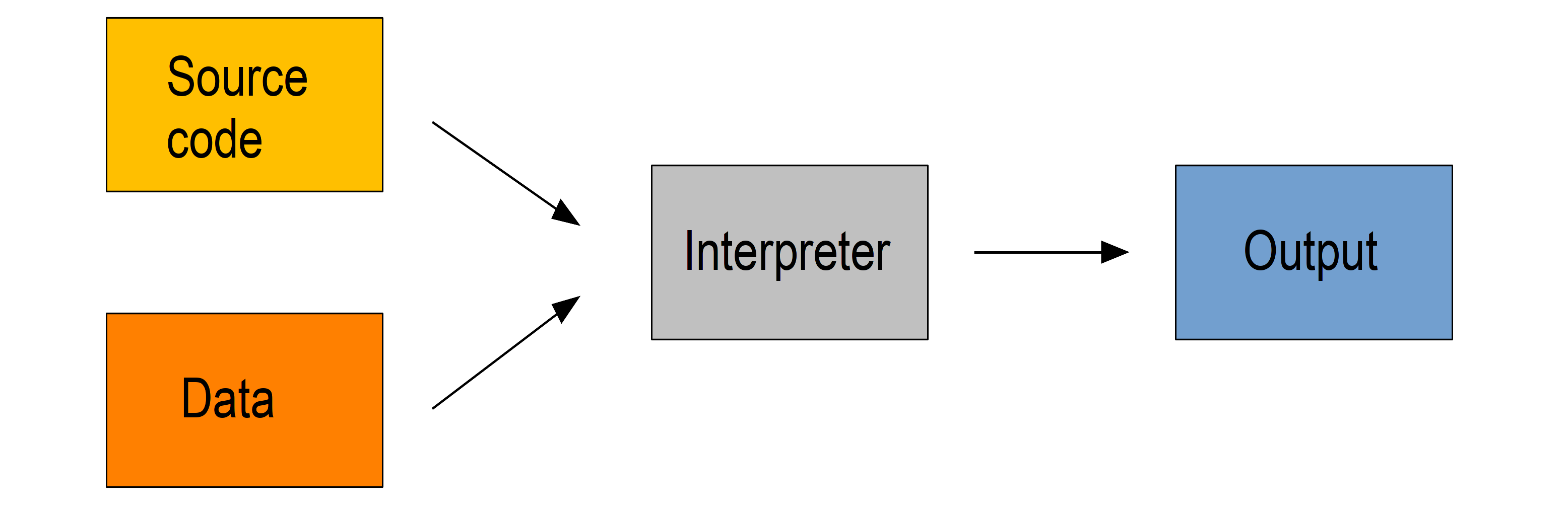

Interpreted languages are executed directly by an interpreter.

Examples of interpreted languages include R, Python, Perl, and JavaScript.

This has many advantages such as dynamic typing and direct feed-back from the code in interactive shells. These languages are also easy to learn.

All this however comes at the cost of efficiency: interpreted languages are slow.

Workflow

So, what do researchers do?

A common workflow, with the constraints of either type of languages, consists of:

- exploring the data and developing code using a sample of the data or reasonably light computations in an interpreted language,

- translate the code into a compiled language,

- finally throw the full data and all the heavy duty computation at that optimized code.

This works and it works well.

But, as you can imagine, this roundabout approach is tedious, not to mention the fact that it involves mastering 2 languages.

Julia

To go back to our initial question as to why a team of computer scientists decided in 2009 to write a new language, Julia is the latest language in the Lisp tradition, attempting to provide an alternative strategy: a single language which is both interactive and efficient.

And it is a very successful attempt.

JIT compilation

Julia uses just-in-time compilation or JIT based on LLVM: the source code is compiled at run time. This combines the flexibility of interpretation with the speed of compilation, bringing speed to an interactive language. It also allows for dynamic recompilation, continuous weighing of gains and costs of the compilation of parts of the code, and other on the fly optimizations.

Of course, there are costs here too. They come in the form of overhead time to compile code the first time it is run and increased memory usage.

Multiple dispatch

In languages with multiple dispatch, functions apply different methods at run time based on the type of all the arguments (not just the first argument as is common in other languages).

Type declaration is optional. Out of convenience, you can forego the feature if you want. This makes it easy to write code. Specifying types however will bring the robustness of static type-checking languages.

Here is a good post on type stability, multiple dispatch, and Julia efficiency.

Metaprogramming

In the tradition of Lisp (again!), Julia has strong metaprogramming capabilities, in particular in the form of macros.