Introduction to high performance research computing with Julia

Abstract

Why would I want to learn a new language? I already know R/python.

R and python are interpreted languages: the code is executed directly, without prior-compilation. This is extremely convenient: it is what allows you to run code in an interactive shell. The price to pay is low performance: R and python are simply not good at handling large amounts of data. To overcome this limitation, users often turn to C or C++ for the most computation-intensive parts of their analyses. These are compiled—and extremely efficient—languages, but the need to use multiple languages and the non-interactive nature of compiled languages make this approach tedious.

Julia uses just-in-time (JIT) compilation: the code is compiled at run time. This combines the interactive advantage of interpreted languages with the efficiency of compiled ones. Basically, it feels like running R or python, while it is almost as fast as C. This makes Julia particularly well suited for big data analyses, machine learning, or heavy modelling.

In addition, multiple dispatch (generic functions with multiple methods depending on the types of all the arguments) is at the very core of Julia. This is extremly convenient, cutting on conditionals and repetitions, and allowing for easy extensibility without having to rewrite code.

Finally, Julia shines by its extremely clean and concise syntax. This last feature makes it easy to learn and really enjoyable to use.

In this workshop, which does not require any prior experience in Julia (experience in another language—e.g. R or python—would be best), we will go over the basics of Julia's syntax and package system; then we will push the performance aspect further by looking at how Julia can make use of clusters for large scale parallel computing.

Software requirements

1 - A terminal emulator and an SSH client for remote access to clusters

Windows:

Install the free Home Edition of MobaXTerm.

MacOS:

Terminal and SSH are pre-installed.

Linux:

You can use xterm or the terminal emulator of your choice.

If SSH does not come bundled with your distribution, install OpenSSH.

2 - The current Julia stable release

3 - A good text editor or the Julia IDE

You will need a capable text editor

(e.g. Emacs, Vim, Visual Studio Code, Sublime, Nano, Atom, Notepad++).

If you would rather play in the Julia IDE, you can find the installation instructions here.

Introducing Julia

Background

Brief history

Started in 2009 by Jeff Bezanson, Stefan Karpinski, Viral B. Shah, and Alan Edelman, the general-purpose programming language Julia was launched in 2012 as free and open source software. Version 1.0 was released in 2018.

Rust developer Graydon Hoare wrote an interesting post which places Julia in a historical context of programming languages.

Why another language?

JIT

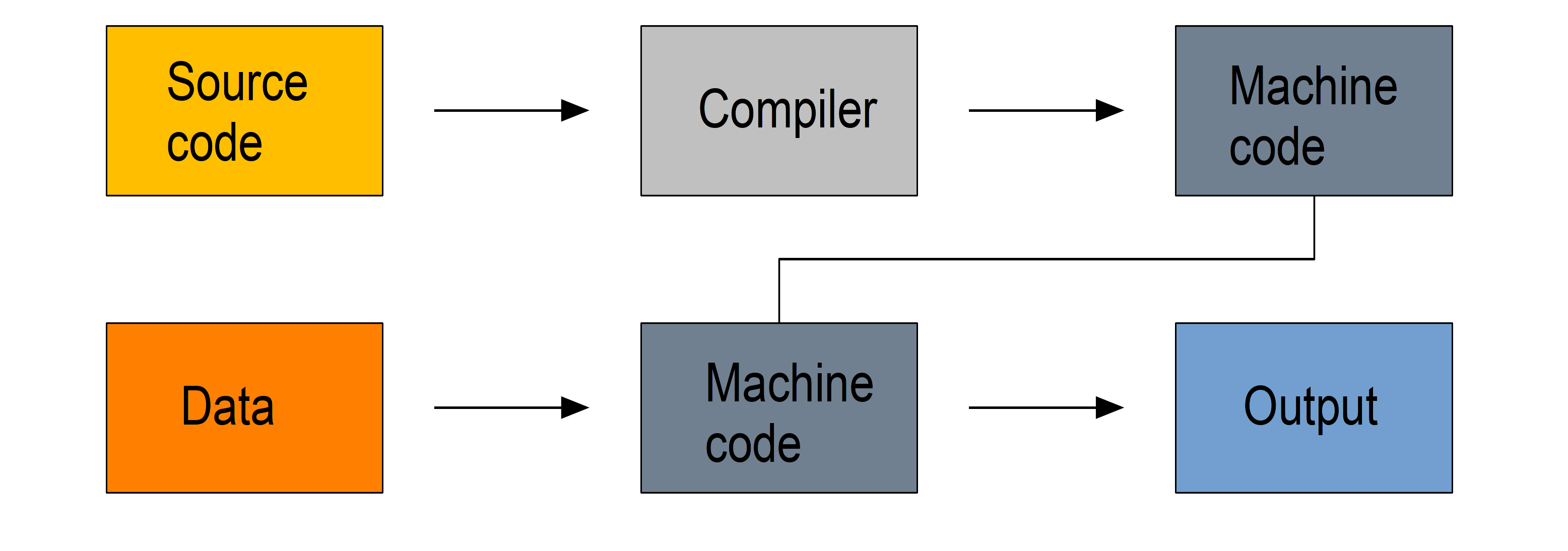

Computer languages mostly fall into two categories: compiled languages and interpreted languages.

Compiled languages

Compiled languages require two steps:

- in a first step the code you write in a human-readable format (the source code, usually in plain text) gets compiled into machine code

- it is then this machine code that is used to process your data

So you write a script, compile it, then use it.

Because machine code is a lot easier to process by computers, compiled languages are fast. The two step process however makes prototyping new code less practical, these languages are hard to learn, and debugging compilation errors can be challenging.

Examples of compiled languages include C, C++, Fortran, Go, and Haskell.

Interpreted languages

Interpreted languages are executed directly which has many advantages such as dynamic typing and direct feed-back from the code and they are easy to learn, but this comes at the cost of efficiency. The source code can facultatively be bytecompiled into non human-readable, more compact, lower level bytecode which is read by the interpreter more efficiently.

Examples of interpreted languages include R, Python, Perl, and JavaScript.

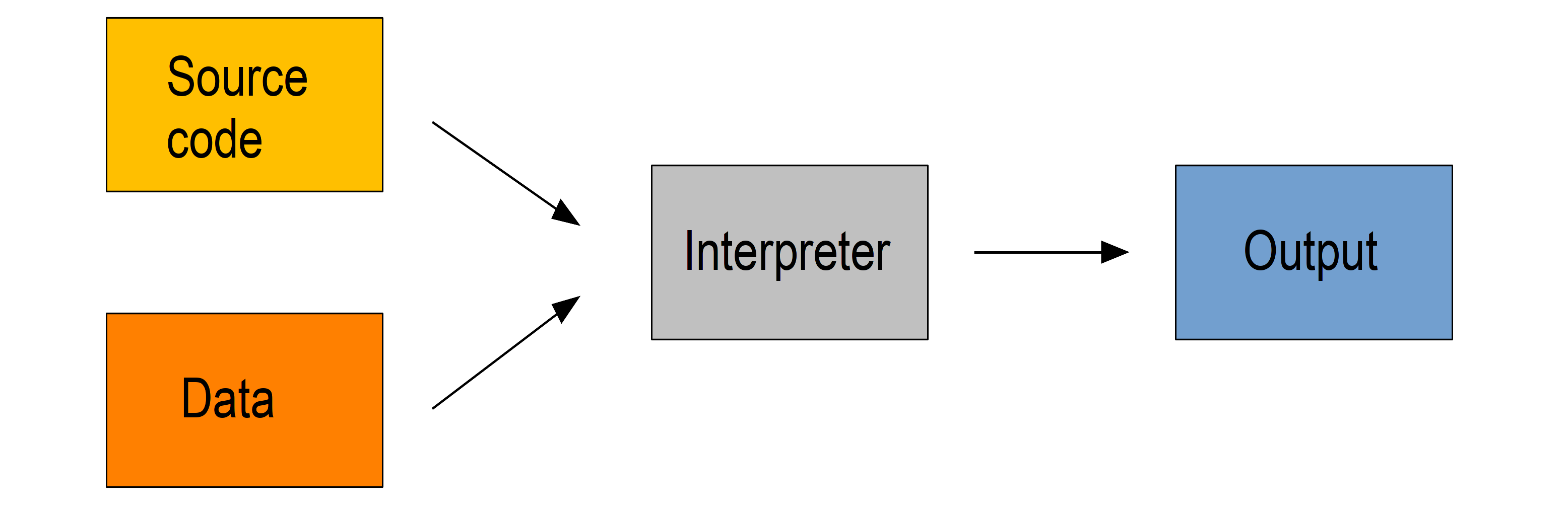

JIT compiled languages

Julia uses just-in-time compilation or JIT based on LLVM: the source code is compiled at run time. This combines the flexibility of interpretation with the speed of compilation, bringing speed to an interactive language. It also allows for dynamic recompilation, continuous weighing of gains and costs of the compilation of parts of the code, and other on the fly optimizations.

Of course, there are costs here too. They come in the form of overhead time to compile code the first time it is run and increased memory usage.

Multiple dispatch

In languages with multiple dispatch, functions apply different methods at run time based on the type of the operands. This brings great type stability and improves speed.

Julia is extremely flexible: type declaration is not required. Out of convenience, you can forego the feature if you want. Specifying types however will greatly optimize your code.

Here is a good post on type stability, multiple dispatch, and Julia efficiency.

Resources

Documentation

Getting help

Interface

Copying and pasting code from a script to the Julia REPL works, but there are nicer ways to integrate the two.

Here are a few:

Emacs

- through the julia-emacs and julia-repl packages

- through the ESS package

- through the Emacs IPython Notebook package if you want to access Jupyter notebooks in Emacs

Jupyter

Project Jupyter allows to create interactive programming documents through its web-based JupyterLab environment and its Jupyter Notebook.

Julia basics

While we will be interacting with Julia through the REPL (read–eval–print loop: the interactive Julia shell) to develop and test our code, we want to save it in a script for future use.

Julia scripts are text files with the extension .jl .

Create a folder called julia_workshop somewhere in your system and create a file julia_script.jl in it.

REPL keybindings

In the REPL, you can use standard command line keybindings:

C-c cancel C-d quit C-l clear console C-u kill from the start of line C-k kill until the end of line C-a go to start of line C-e go to end of line C-f move forward one character C-b move backward one character M-f move forward one word M-b move backward one word C-d delete forward one character C-h delete backward one character M-d delete forward one word M-Backspace delete backward one word C-p previous command C-n next command C-r backward search C-s forward search

In addition, there are 4 REPL modes:

julia> The main mode in which you will be running your code.help?> A mode to easily access documentation.

shell> A mode in which you can run bash commands from within Julia.

(env) pkg> A mode to easily perform actions on packages with Julia package manager.

(env is the name of your current project environment. Project environments are similar to Python's virtual environments and allow you, for instance, to have different package versions for different projects. By default, it is the current Julia version. So what you will see is (v1.3) pkg>).

Enter the various modes by typing ? , ; , and ] . Go back to the regular mode with the Backspace key.

Startup options

You can configure Julia by creating the file ~/.julia/config/startup.jl .

Packages

Standard library

Julia comes with a collection of packages. In Linux, they are in /usr/share/julia/stdlib/vx.x .

Here is the list:

Base64 CRC32c Dates DelimitedFiles Distributed FileWatching Future InteractiveUtils Libdl LibGit2 LinearAlgebra Logging Markdown Mmap Pkg Printf Profile Random REPL Serialization SHA SharedArrays Sockets SparseArrays Statistics SuiteSparse Test Unicode UUIDs

Installing additional packages

You can install additional packages.

These go to your personal library in ~/.julia

(this is also where your REPL history is saved).

All registered packages are on GitHub and can easily be searched here.

The GitHub star system allows you to easily judge the popularity of a package and to see whether it is under current development.

In addition to these, there are unregistered packages and you can build your own.

Try to find a list of popular plotting packages.

You can manage your personal library easily in package mode with the commands:

(env) pkg> add <package> # install <package>

(env) pkg> rm <package> # uninstall <package>

(env) pkg> up <package> # upgrade <package>

(env) pkg> st # check which packages are installed

(env) pkg> up # upgrade all packages

Check your list of packages; install the packages Plots , GR , Distributions , StatsPlots , and UnicodePlot ; then check that list again.

Now go explore your ~/.julia . If you don’t find it, make sure that your file explorer allows you to see hidden files.

Loading packages

Whether a package from the standard library or one you installed, before you can use a package you need to load it. This has to be done at each new Julia session so the code to load packages should be part of your scripts.

This is done with the using command (e.g. using Plots ).

Finding documentation

As we already saw, you can type ?

to enter the help mode.

To print the list of functions containing a certain word in their description, you can use apropos()

.

Example:

> apropos("truncate")Let's try a few commands

> versioninfo()

> VERSION

> x = 10

> x

> x = 2;

> x

> y = x;

> y

> ans

> ans + 3

> a, b, c = 1, 2, 3

> b

> 3 + 2

> +(3, 2)

> a = 3

> 2a

> a += 7

> a

> 2\8

> a = [1 2; 3 4]

> b = a

> a[1, 1] = 0

> b

> [1, 2, 3, 4]

> [1 2; 3 4]

> [1 2 3 4]

> [1 2 3 4]'

> collect(1:4)

> collect(1:1:4)

> 1:4

> a = 1:4

> collect(a)

> [1, 2, 3] .* [1, 2, 3]

> 4//8

> 8//1

> 1//2 + 3//4

> a = true

> b = false

> a + b

What does ; at the end of a command do?

What is surprising about 2a ?

What does += do?

What does .+ do?

> a = [3, 1, 2]

> sort(a)

> println(a)

> sort!(a)

> println(a)

What does ! at the end of a function name do?

Sourcing a file

To source a Julia script within Julia, use the function include() .

Example:

> include("/path/to/file.jl")Comments

> # Single line comment

> #=

Comments can

also contain

multiple lines

=#

> x = 2; # And they can be added at the end of linesA few fun quirks

> \omega # Press TAB

> \sum # Press TAB

> \sqrt # Press TAB

> \in # Press TAB

> \: phone: # (No space after colon. I added it to prevent parsing) Press TAB

> pi

> Base.MathConstants.goldenData types

> typeof(2)

> typeof(2.0)

> typeof("hello")

> typeof(true)Indexing

Indexing is done with square brackets. As in R and unlike in C++ or Python, Julia starts indexing at 1 , not at 0 .

> a = [1 2; 3 4]

> a[1, 1]

> a[1, :]

How can I get the second column?

How can I get the tuple (2, 4) ? (a tuple is a list of elements)

For loops

> for i in 1:10

println(i)

end

> for i in 1:3, j in 1:2

println(i * j)

endPredicates and conditionals

> a = 2

> b = 2.0

> if a == b

println("It's true")

else

println("It's false")

end

# This can be written in a terse format

# predicate ? if true : if false

> a == b ? println("It's true") : println("It's false")

> if a === b

println("It's true")

else

println("It's false")

end

What is the difference between == and === ?

Predicates can be built with many other operators and functions. For example:

> occursin("that", "this and that")

> 4 < 3

> a != b

> 2 in 1:3

> 3 <= 4 && 4 > 5

> 3 <= 4 || 4 > 5Functions

> function addTwo(a)

a + 2

end

> addTwo(3)

# This can be written in a terse format

> addtwo = a -> a + 2

# With default arguments

> function addSomethingOrTwo(a, b = 2)

a + b

end

> addSomethingOrTwo(3)

> addSomethingOrTwo(3, 4)Plotting

It can be convenient to plot directly in the REPL (for instance when using SSH).

> using UnicodePlots

> histogram(randn(1000), nbins=40)Most of the time however, you will want to make nicer looking graphs. There are many options to plot in Julia, but here is a very quick example:

# Will take a while when run for the first time as the packages need to compile

> using Plots, Distributions, StatsPlots

# Using the GR framework as backend

> gr()

> x = 1:10; y = rand(10, 2);

> p1 = histogram(randn(1000), nbins=40)

> p2 = plot(Normal(0, 1))

> p3 = scatter(x, y)

> p4 = plot(x, y)

> plot(p1, p2, p3, p4)Parallel programming

Multi-threading

Julia, which was built with efficiency in mind, aimed from the start to have parallel programming abilities. These however came gradually: first, there were coroutines, which is not parallel programming, but allows independent executions of elements of code; then there was a macro allowing for loops to run on several cores, but this would not work on nested loops and it did not integrate with the coroutines or I/O. It is only in the current (1.3) version, released a few months ago, that true multi-threading capabilities were born. Now is thus a very exciting time for Julia. This is all very new (this feature is still considered in testing mode) and it is likely that things will get even better in the coming months/years, for instance with the development of multi-threading capabilities for the compiler.

What is great about Julia's new task parallelism is that it is incredibly easy to use: no need to write low-level code as with MPI to set where tasks are run. Everything is automatic.

To use Julia with multiple threads, we need to set the JULIA_NUM_THREADS environment variable.

This can be done by running (in the terminal, not in Julia):

$ export JULIA_NUM_THREADS=n # n is the number of threads we want to useOr by launching Julia with (again, in the terminal):

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=n julia

First, we need to know how many threads we actually have on our machine.

There are many Linux tools for this, but here are two particularly convenient options:

# To get the total number of available processes

$ nproc

# To have more information (# of sockets, cores per socket, and threads per core)

$ lscpu | grep -E '(S|s)ocket|Thread|^CPU\(s\)'Since I have 4 available processes (2 cores with 2 threads each), I can launch Julia on 4 threads:

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=4 juliaThis can also be done from within the Juno IDE.

To see how many threads we are using, as well as the ID of the current thread, you can run:

> Threads.nthreads()

> Threads.threadid()For loops on multiple threads

Launch Julia on 1 thread and run the function below. Then run Julia on the maximum number of threads you have on your machine and run the same function.

> Threads.@threads for i = 1:10

println("i = $i on thread $(Threads.threadid())")

endUtilities such as htop allow you to visualize the working threads.

Generalization of multi-threading

Let's consider the example presented in a Julia blog post in July 2019.

Both scripts sort a one dimensional array of 20,000,000 floats between 0 and 1, one with parallelism and one without.

Script 1, without parallelism: sort.jl .

# Create one dimensional array of 20,000,000 floats between 0 and 1

> a = rand(20000000);

# Use the MergeSort algorithm of the sort function

# (in the standard Julia Base library)

> b = copy(a); @time sort!(b, alg = MergeSort);

# Let's run the function a second time to remove the effect

# of the initial compilation

> b = copy(a); @time sort!(b, alg = MergeSort);Script 2, with parallelism: psort.jl .

> import Base.Threads.@spawn

# The psort function is the same as the MergeSort algorithm

# of the Base sort function with the addition of

# the @spawn macro on one of the recursive calls

# Sort the elements of `v` in place, from indices `lo` to `hi` inclusive

> function psort!(v, lo::Int=1, hi::Int = length(v))

if lo >= hi # 1 or 0 elements: nothing to do

return v

end

if hi - lo < 100000 # Below some cutoff, run in serial

sort!(view(v, lo:hi), alg = MergeSort)

return v

end

mid = (lo + hi) >>> 1 # Find the midpoint

half = @spawn psort!(v, lo, mid) # Task to sort the lower half: will run

psort!(v, mid + 1, hi) # in parallel with the current call sorting

# the upper half

wait(half) # Wait for the lower half to finish

temp = v[lo:mid] # Workspace for merging

i, k, j = 1, lo, mid + 1 # Merge the two sorted sub-arrays

@inbounds while k < j <= hi

if v[j] < temp[i]

v[k] = v[j]

j += 1

else

v[k] = temp[i]

i += 1

end

k += 1

end

@inbounds while k < j

v[k] = temp[i]

k += 1

i += 1

end

return v

end

> a = rand(20000000);

# Now, let's use our function

> b = copy(a); @time psort!(b);

# And running it a second time to remove

# the effect of the initial compilation

> b = copy(a); @time psort!(b);Now, we can test both scripts with one or multiple threads:

# Single thread, non-parallel script

$ julia /path/to/sort.jl

2.234024 seconds (111.88 k allocations: 82.489 MiB, 0.21% gc time)

2.158333 seconds (11 allocations: 76.294 MiB, 0.51% gc time)

# Note the lower time for the 2nd run due to pre-compilation

# Single thread, parallel script

$ julia /path/to/psort.jl

2.748138 seconds (336.77 k allocations: 703.200 MiB, 2.24% gc time)

2.438032 seconds (3.58 k allocations: 686.932 MiB, 0.27% gc time)

# Even longer time: normal, there was more to run (import package, read function)

# 2 threads, non-parallel script

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=2 julia /path/to/sort.jl

2.233720 seconds (111.87 k allocations: 82.145 MiB, 0.21% gc time)

2.155232 seconds (11 allocations: 76.294 MiB, 0.54% gc time)

# Remarkably similar to the single thread:

# the addition of a thread did not change anything

# 2 threads, parallel script

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=2 julia /path/to/psort.jl

1.773643 seconds (336.99 k allocations: 703.171 MiB, 4.08% gc time)

1.460539 seconds (3.79 k allocations: 686.935 MiB, 0.47% gc time)

# 33% faster. Not twice as fast as one could have hoped since processes

# have to wait for each other. But that's a good improvement.

# 4 threads, non-parallel script

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=4 julia /path/to/sort.jl

2.231717 seconds (111.87 k allocations: 82.145 MiB, 0.21% gc time)

2.153509 seconds (11 allocations: 76.294 MiB, 0.53% gc time)

# Again: same result as the single thread

# 4 threads, parallel script

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=4 julia /path/to/psort.jl

1.291714 seconds (336.98 k allocations: 703.171 MiB, 3.48% gc time)

1.194282 seconds (3.78 k allocations: 686.935 MiB, 5.19% gc time)

# Even though we only split our code in 2 tasks,

# there is still an improvement over the 2 thread runDistributed computing

Moving on to the cluster

Now that we have some running scripts, let's test them out on our cluster.

Logging in to the cluster

Open a terminal emulator.

Windows users, launch MobaXTerm.

MacOS users, launch Terminal.

Linux users, launch xterm or the terminal emulator of your choice.

$ ssh userxxx@cassiopeia.c3.ca

# enter passwordYou are now in our training cluster.

Accessing Julia

This is done with the Lmod tool through the module command. You can find the full documentation here and below are the subcommands you will need:

# get help on the module command

$ module help

$ module --help

$ module -h

# list modules that are already loaded

$ module list

# see which modules are available for Julia

$ module spider julia

# see how to load julia 1.3

$ module spider julia/1.3.0

# load julia 1.3 with the required gcc module first

# (the order is important)

$ module load gcc/7.3.0 julia/1.3.0

# you can see that we now have Julia loaded

$ module listCopying files to the cluster

$ mkdir ~/scratch/julia_jobOpen a new terminal window and from your local terminal (make sure that you are not on the remote terminal by looking at the bash prompt) run:

$ scp /local/path/to/sort.jl userxxx@cassiopeia.c3.ca:scratch/julia_job

$ scp /local/path/to/psort.jl userxxx@cassiopeia.c3.ca:scratch/julia_job

# enter passwordJob scripts

We will not run an interactive session with Julia on the cluster: we already have julia scripts ready to run. All we need to do is to write job scripts to submit to Slurm, the job scheduler used by the Compute Canada clusters.

We will create 2 scripts: one to run Julia on one core and one on as many cores as are available.

How many processors are there on our training cluster?

Note that here too, we could run Julia with multiple threads by running:

$ JULIA_NUM_THREADS=2 juliaOnce in Julia, you can double check that Julia does indeed have access to 2 threads by running:

> Threads.nthreads()Save your job scripts in the files ~/scratch/julia_job/job_julia1c.sh and job_julia2c.sh for one and two cores respectively.

Here is what our single core Slurm script looks like:

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH --job-name=julia1c # job name

#SBATCH --time=00:01:00 # max walltime 1 min

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task=1 # number of cores

#SBATCH --mem=1000 # max memory (default unit is megabytes)

#SBATCH --output=julia1c%j.out # file name for the output

#SBATCH --error=julia1c%j.err # file name for errors

# %j gets replaced with the job number

echo Running NON parallel script on $SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK core

JULIA_NUM_THREADS=$SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK julia sort.jl

echo Running parallel script on $SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK core

JULIA_NUM_THREADS=$SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK julia psort.jlWrite the script for 2 cores.

Now, we can submit our jobs to the cluster:

$ cd ~/scratch/julia_job

$ sbatch job_julia1c.sh

$ sbatch job_julia2c.shAnd we can check their status with:

$ sqPD stands for pending and R for running.